AUTO-FREE NEW YORK!

Home

Glossary

Light Rail

Regional Rail

Penn Station

Livable City Plan

Books

Links

Donate

|

AUTO-FREE NEW YORK!

| ||||||||

Home |

Glossary |

Light Rail |

Regional Rail |

Penn Station |

Livable City Plan |

Books |

Links |

Donate |

|

Crossing the Hudson by Streetcar By making better use of the Lincoln Tunnel and by taking advantage of new light rail technology, NYC and the region could benefit greatly By George Haikalis Senior Editor, New York Streetcar News Webmaster's note: this proposal first appeared in the March/April 1995 issue of the New York Streetcar News. Much has changed transit-wise in the NY metro region since that time, including the completion of the Kearny rail connection in New Jersey, the opening and successful operation of the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail line, also in New Jersey, and the dreary postponement of the 42nd Street LRT proposal, mentioned below. But one thing hasn't changed - NYC's chronic traffic jams! A revision of this proposal to reflect these and other changes is in the works.

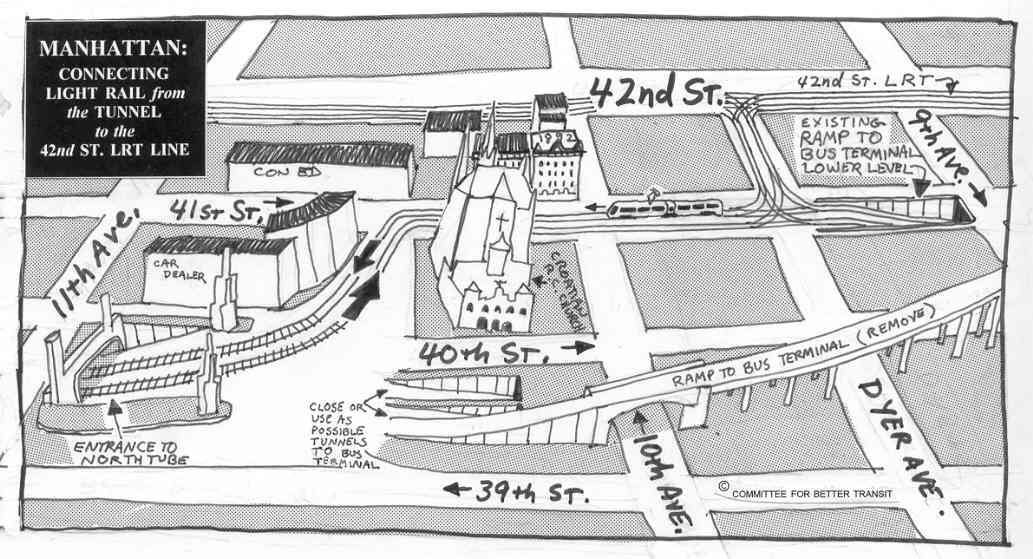

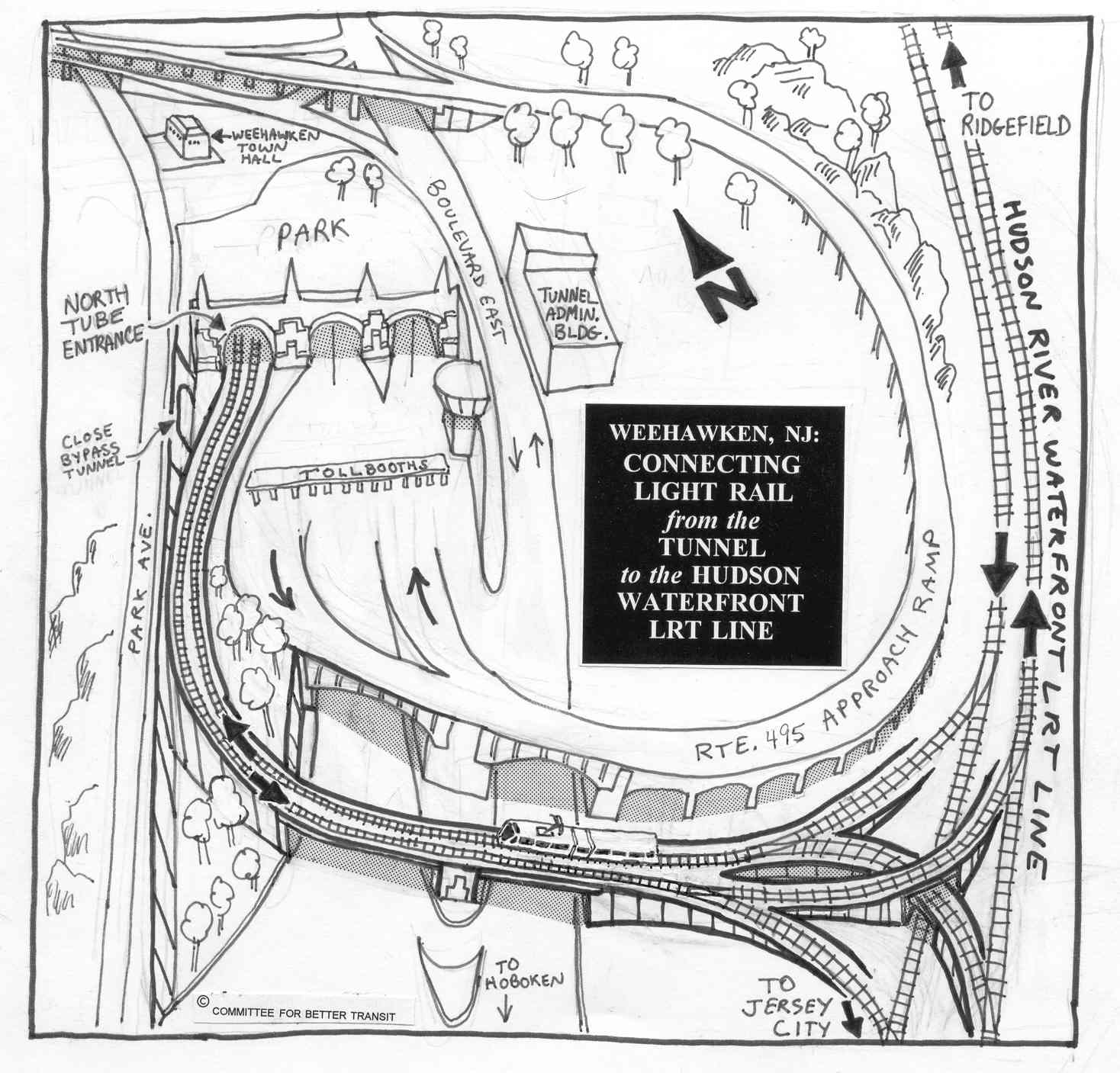

EVERY WEEKDAY MORNING OF THE YEAR, radio traffic newscasts routinely report lengthy back-ups of motor vehicles on the New Jersey approaches to the Lincoln Tunnel. Thirty minute delays are the norm, one hour waits not uncommon. In the evenings, the situation is reversed, with Manhattan's Chelsea and Clinton neighborhoods flooded with cars. More than half of the thousands of private cars in these tie-ups carry only a single person, the driver, sitting fidgeting in the exhaust fumes. With the region's longest back-ups, this absurd system is by far the most polluting and inefficient way to move people that our society has ever invented. Some motorists say they have little choice. For most trips to midtown Manhattan, travelers from northern and western New Jersey and from Orange and Rockland Counties in New York do not have an attractive rail option. For these commuters, taking the bus is clearly a second-class choice, even though herds of buses using the express bus-only lane on the Route 495 tunnel approach bypass the long line of cars and trucks stuck in traffic. Studies have shown travelers are 50 percent more likely to choose cars over transit where rail options are poor or non-existent. But this could change soon. Out in the Meadowlands, 2,500 feet of track -- the "Kearny Connection" -- is now under construction that will enable motorists from Morris and Essex Counties to switch to direct high speed trains to Penn Station in midtown Manhattan for work, shopping or entertainment. A new transfer station at Secaucus and a new track connection in Montclair will speed commuters from Passaic County and western Bergen County into midtown. Finally, construction is expected to begin in 1996 on both the long-awaited Hudson-Bergen waterfront light rail line, and on the 42nd Street crosstown light rail line. But there still won't be a direct track connection between these two light rail lines, barely a mile apart on either side of the Hudson River. To connect them with a new tunnel will cost a fortune and take years, perhaps decades, to plan and build. For the time being, light rail commuters will have to settle for transfers to and from the Port Imperial Ferry that now operates from Weehawken to W. 38th St. The inconvenience of a double transfer will hold down ridership levels. The quickest and most economical way to interconnect these two light rail lines is to lay track in and to operate streetcars through the Lincoln Tunnel. This trans-Hudson light rail plan can vastly improve transit service and provide major relief from the automobile chaos plaguing New York and northeast New Jersey. It would help the region meet health-oriented federal clean air regulations, create jobs and boost the economy by making it easier for essential car and truck traffic to reach the region's core. Road Expansion is Anti-PlanningThe development of the Lincoln Tunnel complex over the years is one of the most dramatic examples of urban anti-planning that New York has to offer. Eighty years of building non-rail tunnels have proven to be a disaster for the city and especially west midtown. This tunnel generates much more car and truck traffic than Manhattan's streets can handle. The bus terminal's spaghetti of approach ramps occupy acres of precious midtown real estate, while the non-stop noise and diesel fumes make life miserable for the thousands of residents of Clinton in Manhattan and Weehawken in New Jersey. Built and operated by the Port Authority, the Lincoln Tunnel is actually three separate tubes, each of which has two lanes. The first tube, opened in 1939, was heralded as a symbol of progress and a permanent relief from congestion. Before 1939, to cross the mile-wide Hudson River, cars and trucks used the Holland Tunnel (three miles south) or the George Washington Bridge (seven miles north). Residents not using cars, who lived along the densely populated palisade area along the Hudson River in New Jersey, rode streetcars down the bluff to Weehawken and transfered to ferries that terminated at the foot of 42nd St. in Manhattan. Here they would board crosstown streetcar lines. The Lincoln Tunnel changed this. Private bus companies sprang up, using diesel buses, a 1930s technology development, directly to terminals in the Times Square area. (One ambitious operator even requested a franchise from the Port Authority for the right to install tracks in the tunnel!) Although the first tube was supposed to relieve congestion, it was soon overwhelmed. With the promise of an end to traffic jams, a second two-lane tube was completed in 1945. As streetcar lines were shut down, bus companies expanded, resulting in a bewildering array of bus stations and loading zones. Rather than consider a rail tunnel that could have connected to New York's subways, the Port Authority built a large and costly bus terminal/car parking garage at 41st St. and 8th Ave. in 1950. The 1950s brought rapid growth in suburban sprawl upon the New York metropolitan region. Without corresponding rail improvements, private car use skyrocketed. A third two-lane tube, opened in 1956, was the last new highway constructed into Manhattan's Central Business District. As with the first two tubes, it was supposed to reduce traffic, yet only encouraged even more motorists to drive into midtown. Two additions to the bus terminal/car parking garage followed, as the Port Authority relentlessly pursued more highway building.Proclaiming Emancipation from CongestionThe Committee for Better Transit's plan calls for installing light rail tracks only in the two-lane north tube of the Lincoln Tunnel. The north tube is the most promising because the track connections to it would be the simplest. In Weehawken, the tracks would link directly to NJ Transit's planned waterfront light rail line, permitting direct routes north to Ridgefield and south to Hoboken, Jersey City and Bayonne. In Manhattan the tracks would be linked to the 42nd St. light rail line at Dyer Ave., a short street between 9th and 10th Avenues. A spur would use an existing portal on 41st St. to enter the lower level of the Port Authority Bus Terminal. The northern half of this lower level would be converted to a light rail terminal. There would be two different rail services through the tunnel to serve two different travel markets. One service, using smaller two-car trains, would connect the 42nd St. light rail line with the Hudson River waterfront line. The other service, using larger four-car trains, would bring light rail vehicles from a new network of routes directly into part of the former bus terminal. West of the Hudson, many extensions to the initial route are possible. The line could follow the Susquehanna rail line from Ridgefield north to Hackensack and onto NJ Transit's Pascack Valley line to Spring Valley in Rockland County, New York. A light rail replacement for this peak hour-only commuter rail line would allow all-day, frequent, high speed light rail service directly to midtown Manhattan. The lay-up yard in Rockland County, where NJ Transit's diesel locomotives presently idle all night, creating a community nuisance, would be converted to a more environmentally friendly light rail yard. Another branch line, to Tenafly and eventually to Nyack, would follow the "Northern Branch," a former commuter rail line which is now a little used freight line. Another could peel off at Ridgefield Park and use two abandoned trackbeds of the former four-track "West Shore" commuter line to Dumont. From Hackensack a route west along the Susquehanna line could connect with, and supplement, the NJ Transit commuter rail line to Radburn, Ridgewood and Suffern. Another spur could swing onto Broadway in Paterson, giving that city's moribund center a much needed boost. All told, some 68 route miles of light rail line could be installed at relatively low cost on existing commuter or freight trackage in Bergen, Passaic and Rockland Counties. Over fifty rail stations would be linked by high speed light rail directly to midtown Manhattan, as well as to points along New Jersey's waterfront. The Jersey Meadowlands Sports Complex is just over two miles due west from the light rail line location in North Bergen. This major destination could be easily reached by a light rail spur on an elevated guideway or in the median of Route 3. We believe that most of today's bus commuters (and many car commuters) would gladly switch to this form of direct light rail service. Four-car light rail trains to the converted bus terminal could handle as many as 600 persons per train. Each two-car train across 42nd St. could accommodate 300 passengers. If at peak hours each service ran every two minutes, for a combined one minute headway through the tunnel, a total of 27,000 peak hour, peak direction travelers could be served. Additional Manhattan distribution routes, for example along 34th St. and Broadway, as suggested by the Regional Plan Association, could provide even more capacity. The tunnel segment, the busiest part of the route, would run non-stop, maximizing its capacity. It would feature a modern high capacity "moving block" signal system like the ones used in Vancouver, Canada and Lille, France. Such a system is also being installed in San Francisco's Market Street light rail tunnel. But Where Would All The Cars Go?Although it's hard to conceive that taking away part of the Lincoln Tunnel from motorists could reduce congestion, a little number crunching will make it clear (traffic statistics are not rocket science). In 1992, during a typical morning peak hour, 4,100 cars, vans and trucks carrying about 7,000 persons and 730 buses carrying 28,000 persons used the Lincoln Tunnel to enter Manhattan on four inbound lanes (two lanes of the six lanes are reversed in the peak direction). That's 4,100 plus 730 equals 4,830 vehicles. If two of these lanes are converted to light rail, then only two inbound lanes remain, cutting motor vehicle volume in half. That's 4,830 divided by two equals about 2,400. Assuming that the number of trucks and buses, which take up roughly twice the road space as cars, stayed constant, then all of the decline would have to occur in private car use. There would be room for only about 500 cars, or 14 percent of the current total. But if we assume that about 90 percent of current bus travelers switch to the new direct Penn Station rail services, or to the complete 70-mile light rail network outlined earlier, then there would be room in the tunnel for about half of the cars that now use the tunnel. Some 1,800 peak hour motorists would have to switch to the enormously improved public system. Over the full peak period that the tunnels are operated with four lanes inbound this would add up to nearly 10,000 motorists. Tolls are another factor. The best way to assure that only essential cars and trucks use the tunnel, with its reduced vehicular capacity, would be to increase peak period toll rates. The increased revenues could make up for those lost when motorists diverted to transit, and could help to cover the cost of the new light rail system. Another source of funding would be the substantial operating cost savings resulting from substituting light rail for bus. For example, 120 trolley operators could do the work of 1,400 bus drivers in the three hour morning peak period. The bus terminal, in a prime location on a rejuvenated 42nd St., would be converted to some other commercial use except for the basement, half of which would be for light rail and the other half retained for long distance buses. The bus ramps leading to the terminal could be demolished and replaced with new housing or other tax paying buildings. Since electric streetcars emit no fumes, much of the north tube's ventilating system could be shut down, saving enormous amounts of electricity. With inbound car traffic from the Tunnel cut in half, today's chronic traffic chaos will be sharply reduced. Noise and air pollution would subside, the neighborhood would revive, property values would rise and trees and shrubs could grow again. Community anxieties about traffic displaced off of 42nd St., to accommodate the trolley there, will be eased. Streetcars across the Hudson makes a lot more sense than the existing system. Everyone will benefit because travel will be easier and more fun between the two states, encouraging new trips and new economic activity not only in Manhattan but in Hackensack, Paterson and other cities as well.Return to the Auto-Free NY home page.

© Copyright 2005, 2006. All rights reserved. Auto-Free New York.

|